What are paradigms?

Towards systemic design for paradigm change through quantum theory

Paradigms are fundamental forces in systems and sources of systemic change... yet despite their legendary status, they remain poorly defined. This interactive exploration reveals their structure, dynamics, and implications for systemic design.

Explore the Theory →Methods

This project emerged from examining Donella Meadows's conceptualization of paradigms as leverage points through the lens of Karen O'Brien's quantum social change, using transdisciplinary design synthesis and disciplined imagination to develop new theory.

Theoretical Foundations

The inspiration for this project combines two perspectives: In "Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System," Donella Meadows positioned paradigms as the most powerful leverage points for systemic change while cautioning they are also the hardest to change. In 2024's You Matter More Than You Think, Karen O'Brien (2024) argued that our approach to changemaking itself falls under a paradigm ill-informed by classical physics, demonstrating how quantum theoretic concepts may provide a valuable alternative paradigm for insights into how change happens in complex systems—what she called "Quantum Social Change."

Transdisciplinary Design Synthesis

I applied Jon Kolko's (2010) design synthesis process, underpinned by Karl Weick's (1989) disciplined imagination as a framework for theory development. This process synthesized strong theory by integrating constructs from multiple disciplines through reframing, concept mapping, and insight combinations.

I asked: "What if paradigms had quantum properties and dynamics?" and sought relevant concepts from quantum theory through this top-down frame, collecting data to find relationships and themes applicable to understanding paradigms and paradigm change.

Disciplined Imagination

Following Weick's guidance, I emphasized imaginative, diverse constructs rather than weaker conceptualizations that would be easier to validate. This artificial selection of theories helped develop rich, elegant theory through:

- Descriptive and diverse problem statements exploring paradigms from fundamental perspectives (Meadows, Kuhn)

- Diverse thought trials consisting of if-then statements: "If this quantum concept applied to paradigms, then this is how they would be described"

- Selection criteria of relevance (isomorphic or metaphorical similarity) and utility (usefulness in characterizing paradigm behavior and dynamics)

Practical Process

I reviewed literature on paradigms and quantum theory using convenience sampling, following references to explore related concepts. I collected, related, and contrasted concepts, collating them into clusters addressing the research questions. Three exemplary systemic issues provided lightweight utility testing: parenting (managing young children's behavior), higher education (with generative AI), and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

I iteratively refined the model when new concepts passed the selection criteria, continuing until reaching conceptual saturation. The resulting model is presented here for further critique as the next "artificial selection" test of the theory's strength.

The Problems of Paradigms

Understanding paradigms requires confronting fundamental questions about their nature and how they change. Two key problems emerge from examining paradigms as leverage points and as objects of revolutions.

Problem 1: Where Do Paradigms Come From?

Meadows positioned paradigms as the most powerful leverage points for systemic change—the deepest beliefs about how systems work. Yet she provided little guidance on their phenomenological origins.

To explore Meadows’s thinking with an example: in a given family, kids must behave respectfully lest they be disciplined. However, there is no instruction manual nor rule book defining what respectful behaviour is. Consider how this may govern behaviour of the social system through a basic balancing feedback loop: if a child’s behaviour becomes increasingly "disrespectful," they are increasingly "disciplined" until the behaviour returns to an acceptable level from the disciplinarian. That is how this paradigm would act as the “source of the system” (Meadows, 1997, p. 18, para. 2), illustrating Meadows’s commentary on both the importance and difficulty of paradigms.

Meanwhile, imagine that a single member of the household experiences a paradigm shift — for instance, to a paradigm that prioritizes connection over correction, involving e.g., validating children’s feelings and behaviours (see e.g., Becky Kennedy's Good Inside 2022). Note how this change, while dramatic for one member of the family, would be unlikely to change the overall system’s behaviour unless the other members of the household also start following the new paradigm.

Now we come to an important question and the crux of the problem with Meadows’s conceptualization of paradigms: where, phenomenologically, do the paradigms come from in the above example? I have described some of the events and actors in the system: the kids and their behaviour, the parents and their disciplinary responses, the concept of boundaries, and the individual beliefs and understanding that each parent and kid may have. Notice that none of these specific phenomena are a paradigm! Moreover, how can the parent whose paradigm has shifted work to change the paradigm of the whole family system?

Meadows advised to "keep pointing at anomalies in the old paradigm" and "speak louder from the new one," but offered vague guidance on practical intervention. How do you make someone open-minded? How do you help someone become an active change agent? These difficulties underscore the need to develop methods for changing and transcending paradigms.

Paradigms themselves seem to be systems—systemic, relational phenomena manifested by specific combinations of beliefs and behaviors.

Problem 2: What Changes First—Paradigm or System?

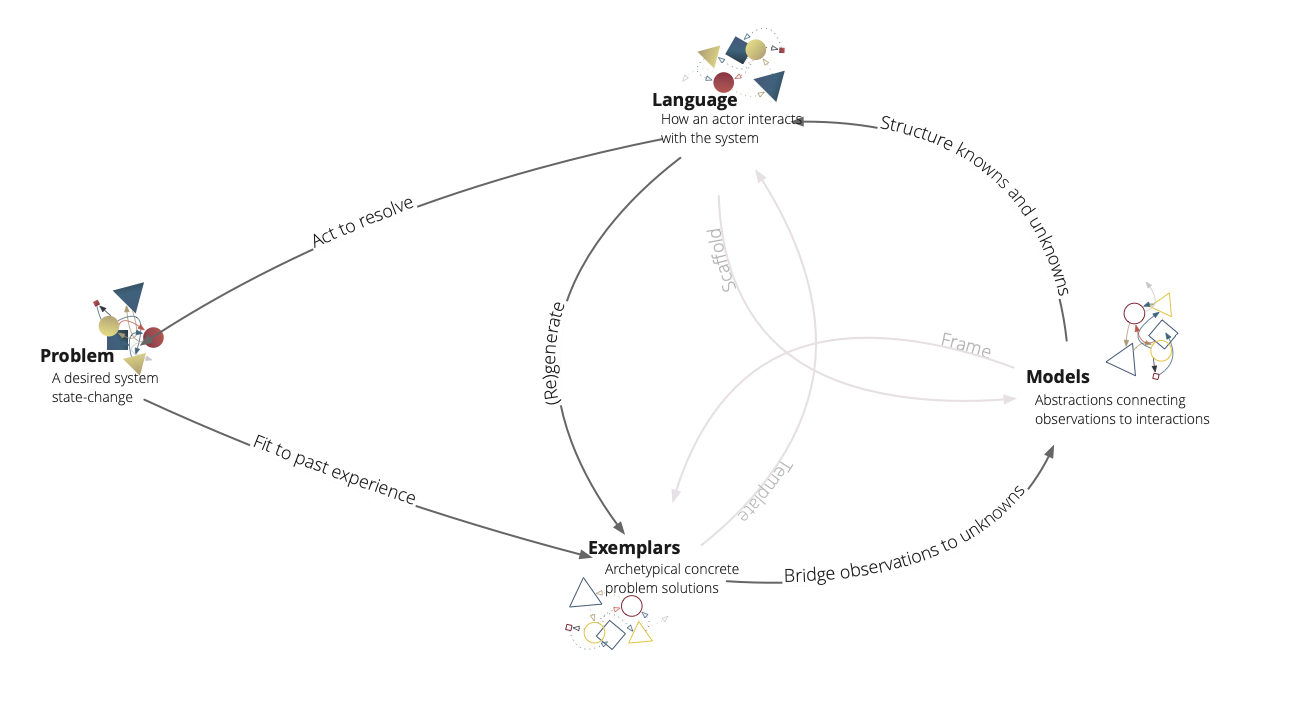

Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions underscored the role of paradigms as how change happens in scientific disciplines. In the book, he defined paradigms as disciplinary matrices composed of: (1) special formalisms of language and symbols, (2) models of phenomena, and (3) exemplars (key problems and their solutions). He also called Exemplars "small paradigms," emphasizing the role they play in helping learners practice applying the paradigm's models and formalisms, integral to accessing a discipline's cognitive achievements.

In "Second Thoughts on Paradigms", a 1977 article, Kuhn resolved that paradigm shifts likely happen through small evolutions more than dramatic revolutions—iteratively changing as communities find new niches of exemplars unsolvable with old paradigms. His disciplinary matrix provides a pragmatic conceptualization: if paradigms are the source of systems, they must emerge from interactions between language, models, and exemplars.

But which changes first? Does changing the relational system of exemplars, models, and language drive paradigm shifts, or do paradigm shifts change the language, models, and exemplars used in the system?

Quantizing Paradigms: A Quantum-Like Approach

Following Karen O'Brien's exploration of quantum-like modelling of social change phenomena, I explored how paradigms exhibit quantum-like properties to find new ways to understand these super-systemic phenomena. Rather than directly applying quantum physical formalisms, I sought metaphorical and isomorphic parallels between paradigms and quantum theory phenomena.

Quantum systems consist of elemental objects with discrete values that evolve through environmental interactions. Similarly, paradigms are "emitted" or manifested in discrete components—the language, models, and exemplars that comprise them. Paradigms are discrete all-or-none phenomena: for any individual interacting with a system at a given moment, a paradigm either is the source of the system or it isn't.

This quantum-like lens reveals paradigms as exhibiting fundamental duality—existing simultaneously as waves of belief and particles of practice.

Paradigmatic Beliefs

Beliefs that constrain and enable other beliefs about a system's causality and teleology.

Theories of Causality

What causes what? How do elements in the system influence each other? Understanding the chains of cause and effect that shape system behavior.

Theories of Action

How should one act on the system? What interventions are possible? Beliefs about the right ways to create change and achieve desired outcomes.

Theories of Systemic Change

Why do things happen? What drives transformation in the system? Understanding the deeper patterns and forces behind system evolution.

These beliefs constitute an individual's theories of systemic change and action—what causes what, why things happen, and how one should act on the system.

Paradigmatic Matrix

The set of relations between Exemplars, Models, and Languages that manifest and shape paradigmatic beliefs.

Exemplars

Concrete problem solutions documenting previously-encountered problem resolutions. Archetypical state transitions showing similar problems and how they were (or were not) successfully resolved.

Models

Isomorphic and metaphorical abstractions that bridge observations of "what is" to hypotheses of "what could be." Create compact descriptions of complex phenomena, connecting system observation with action.

Languages

Symbols, grammars, and scripts used to represent and act on the system. Includes any action or artifact used to conceptualize the system, the problem at hand, the goal-state, and possible interventions.

These elements form a system of interacting components that both express and teach the paradigm. They are boundary objects that triangulate beliefs across individuals.

The Wave-Particle Nature of Paradigms

Drawing from quantum theory, paradigms exhibit a fundamental duality: they exist simultaneously as waves of potential and particles of practice. Understanding this duality reveals how paradigms both constrain and enable action.

The Wave Function: Potential Causality

Before you encounter a problem, your paradigm exists as a wave—a superposition of all possible Languages, Models, and Exemplars you might employ. Like quantum particles, these elements exist in multiple states simultaneously, each with different propensities.

The paradigm-as-wave doesn't specify exactly which language you'll use or which model you'll apply. Instead, it contains the entire probability space of your potential responses.

Wave Collapse: The Act of Observation

When you encounter a specific problem—when you "measure" the reality of your system by interacting with it—the wave function collapses. Your paradigm crystallizes into specific, observable particles: the concrete exemplars you reference, the specific model you apply in sensemaking, and the particular languages you act with.

This collapse isn't random. It's weighted by your paradigm's wave function—your history, training, and past successes. But until the moment of collapse, multiple possibilities coexist.

Wave Form

Before you encounter a specific problem, your paradigm exists as a wave of potential—flowing beliefs about causality, action, and systemic change. These are the theories you hold about how systems work and how you should interact with them: your theories of systemic change and action.

Theories of systemic change & action

The wave represents: All possible ways you might understand and respond to situations within this paradigm. Your beliefs exist as distributed potential until called upon.

Particle Form

When you encounter a specific problem requiring action, the wave collapses. Your paradigm manifests as specific, observable particles: the Languages, Models, and Exemplars you use to make sense of and act on the situation.

Languages

The specific words, symbols, and scripts you use

Models

The metaphors and abstractions you apply

Exemplars

The past solutions you reference

The particles represent: The discrete, measurable elements of your paradigm in action. These are what others can observe and interact with.

Collapse the wave of paradigmatic beliefs into particles

Interactive Wave Collapse Simulation

Watch how paradigmatic waves collapse into specific Languages, Models, and Exemplars when encountering problems. Each collapse shows different relationships and cascading effects.

Scroll down to observe a system...

Languages

Specific symbols and scripts

Models

Metaphors you apply

Exemplars

Past solutions you reference

Wave Function

A paradigm's wave function describes all the possible Languages, Models, and Exemplars that could emerge from one's beliefs. It's the potential space of tghe paradigm—what someone might say, think, or do given the opportunity to interact with the system.

- Exists as distributed probability

- Contains all possible paradigmatic responses

- Shaped by your theories of causality and action

Wave Collapse

The moment someone needs to act—when a problem demands response—their paradigms' waves collapse. Specific Languages, Models, and Exemplars crystallize from the field of possibilities. This is paradigm-in-action.

- Triggered by encountering a problem

- Produces observable, discrete elements

- Influenced by context and prior experience

Complementarity

Like quantum phenomena, one cannot precisely observe both the wave (beliefs) and particles (Languages, Models, and Exemplars) simultaneously. When someone is using specific Languages, Models, and Exemplars, they are changing the beliefs that generated them. When they are reflecting on beliefs, they are doing so through manifesting their beliefs as Exemplars, Models, and Languages.

Measurement Changes the System

Every time someone "uses" a paradigm—every collapse into specific Languages, Models, and Exemplars—they reshape the paradigm itself. Success reinforces certain patterns in the wave function. Failure creates new possibilities. The act of observation is never neutral.

Why This Matters

Understanding paradigms as wave-particle phenomena helps explain their paradoxical nature: they're simultaneously stable (the wave persists) and changeable (each collapse reshapes the wave). You can't directly change someone's paradigm-as-wave, but you can influence the particles they produce—and through repeated collapses with different outcomes, the wave itself gradually transforms.

For changemakers: Focus on changing the contexts that trigger wave collapse and the feedback from collapsed particles. Shape the problems people encounter and the success of the Languages, Models, and Exemplars they use.

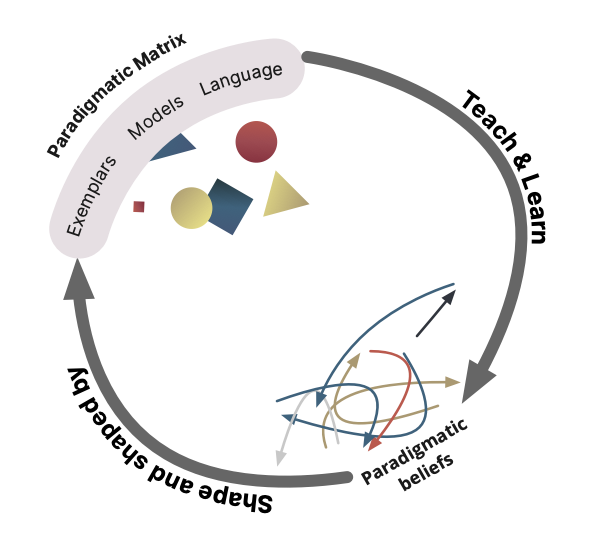

The Paradigm Change Cycle

Paradigms are regenerative systems. The cycle operates through continuous feedback between beliefs and the paradigmatic matrix.

Encounter Problem

An individual encounters a problem in a system—a desired state transition that requires action.

Generate Exemplars, Models, and Languages

Their paradigmatic beliefs generate specific Exemplars, Models, and Languages for understanding the problem.

Guide Action

These Exemplars, Models, and Languages elements guide how they understand the system and determine appropriate actions.

Reshape Beliefs

Actions produce outcomes that reshape paradigmatic beliefs through success or failure feedback.

Become Boundary Objects

When shared with others, Exemplars, Models, and Languages elements become boundary (negotiating) objects that shape collective paradigms.

Collective Feedback

Observations of collective paradigms constrain and enable individual paradigms in turn.

This regenerative cycle shows how paradigms are not static belief systems but dynamic processes of continuous adaptation and evolution through practice.

How Paradigms Change

Paradigms cannot be changed directly. Instead, they change through evolutionary and revolutionary processes as their constituent elements—Language, Models, and Exemplars—change.

Individual Level

Individuals find new Exemplars, Models, and Languages that better fit their experience and goals. Success with these new elements reshapes their theories of systemic change and action.

Collective Level

As individuals demonstrate the effectiveness of their paradigmatic Exemplars, Models, and Languages in solving important problems, others observe this success (or failure) and it may resonate. These observations reshape others' individual beliefs, emerging into new, evolutionary collective paradigms.

Boundary Objects

Exemplars, Models, and Languages elements act as boundary negotiating objects—simultaneously expressing paradigms and evolving them through use. Shared exemplars, models, and language triangulate different individual beliefs into collective understanding. At the same time, collectively-held paradigms constrain and emphasize the paradigmatic beliefs held by individuals.

Paradigm change happens not through direct intervention but through the gradual or sudden transformation of the Exemplars, Models, and Languages that constitute and teach the paradigm.

Key Implications

Understanding paradigms as dual systems with constituent elements has profound implications for how we approach systemic change and transition design.

Paradigms are a false leverage point

Paradigms are not a leverage point. They are themselves dynamic systems of entangled relations. We must ask “which elements of the paradigm’s matrix have the most leverage over the paradigm?”

Paradigm change is a process, not an event

Paradigm shifts are processes composed of discrete intra-active events. Change occurs through accumulated alterations in Language, Models, and Exemplars. Each change evolves the paradigm; true revolutions may be rare.

Wicked problems resist paradigm change

Paradigm change is particularly difficult for wicked problems. Paradigm change depends on the interaction between each of the components of the matrix, including exemplars — which are proven, demonstrated solutions. Thus finding new belief-reinforcing events is hard. What is an exemplar of stopping climate change?

The Bottom Line: Paradigms are neither mystical nor unchangeable. They are systems we can understand, map, and — perhaps! — thoughtfully redesign.

Next Steps

This dual model of paradigms opens new avenues for research and practice. Four key directions emerge from this work, each building on the foundations established here.

Design methods for paradigm change

I have presented a pragmatic dual model of paradigms, but the fundamental question is whether this model may be used to develop clear and robust methods for the systemic design of paradigm change. Can future design research develop techniques, tools, and principles that may be used to guide effective and sustainable paradigm shifts?

Validating the model and theory

The paradigmatic matrix of Language, Models, and Exemplars could be missing essential components. We need empirical investigation to test whether these three quanta sufficiently explain paradigm dynamics, or whether additional elements are required. What other quantum-like properties might reveal hidden structure in how paradigms cohere and evolve?

Extending quantum-like modelling

The quantum social systems approach proved generative for understanding paradigms. This suggests potential application to other phenomena in systemic design. Where else might concepts like superposition, entanglement, and measurement collapse illuminate dynamics that classical models obscure?

Disciplined imagination with transdisciplinary design synthesis

This paper's methodology—combining design synthesis with disciplined imagination across quantum physics and paradigm theory—produced novel insights but remains implicit. Explicit documentation of this transdisciplinary design synthesis process could establish it as a replicable methodology for theory construction in other domains.

The Research Continues: These next steps represent pathways from theory to practice, from understanding to intervention, from model to method. Each direction invites collaboration across disciplines to deepen our capacity for designing transformative paradigm change.