Design

Journal-Article_Conference-Paper

205 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

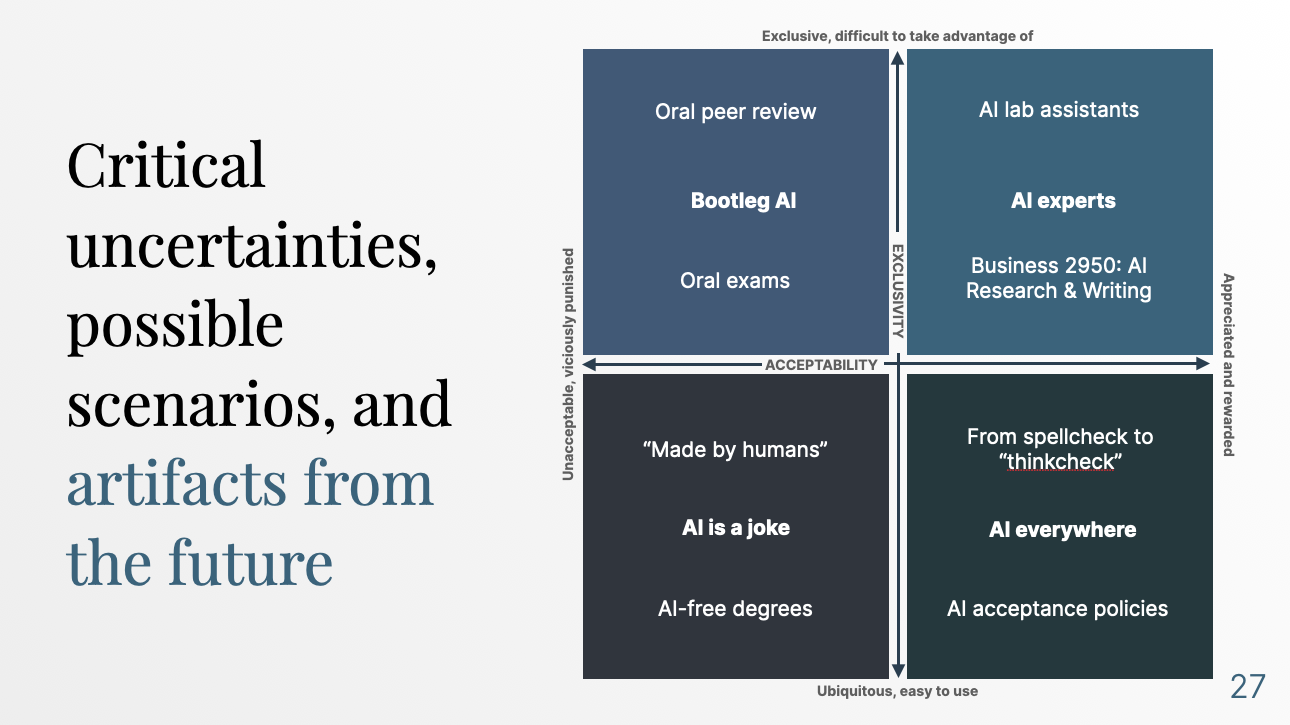

Signals_Trends_Drivers_Scenarios

185 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Instructions_Advice_Guidelines

179 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Research-Methods

139 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Theory

128 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Opinion_Thought-Piece

118 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

News

102 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Frameworks

67 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Highlights

53 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Workflows

53 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Data

52 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Book_Chapter

38 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Strategy

35 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Diagrams

28 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Philosophy

26 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Policy

25 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Stories

25 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Apps-or-Tools

23 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Tech

23 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Systemics

21 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Design

18 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Automation

17 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Systems

17 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Obsidian

16 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Articles

15 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Platforms

15 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Projects

13 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Research

13 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Change

12 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Poetry_Quotes

11 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

Systemic Design

11 notes with this tag (showing first 10 results)

.Topic

10 notes with this tag

Productivity

10 notes with this tag

Shortcuts

10 notes with this tag

Innovation

8 notes with this tag

Education

6 notes with this tag

Futures

6 notes with this tag

PKM

6 notes with this tag

Systemic Change

6 notes with this tag

Systemic Strategy

6 notes with this tag

Systems Sketching

6 notes with this tag

DEVONthink

5 notes with this tag

Podcasts

5 notes with this tag

University

5 notes with this tag

.Presets

4 notes with this tag

Apps

4 notes with this tag

Complexity

4 notes with this tag

Ember/Projects

4 notes with this tag

Presentations

4 notes with this tag

Science

4 notes with this tag

Changemaking

3 notes with this tag

Crowdsourcing

3 notes with this tag

Integrated Thinking Environments

3 notes with this tag

Psychology

3 notes with this tag

Talks

3 notes with this tag

Tools

3 notes with this tag

3 notes with this tag

Academia

2 notes with this tag

AI

2 notes with this tag

Bookends

2 notes with this tag

Climate Change

2 notes with this tag

Conversations

2 notes with this tag

Creativity

2 notes with this tag

Ethics

2 notes with this tag

Ethnography

2 notes with this tag

Getting Things Done

2 notes with this tag

Guide

2 notes with this tag

Information Systems

2 notes with this tag

Knowledge Innovation

2 notes with this tag

Leverage

2 notes with this tag

Meta

2 notes with this tag

Methods

2 notes with this tag

Note-Taking

2 notes with this tag

Personal Knowledge Management

2 notes with this tag

Privacy

2 notes with this tag

Procrastination

2 notes with this tag

Reading

2 notes with this tag

Social Media

2 notes with this tag

.Used

1 notes with this tag

Academy

1 notes with this tag

Activism

1 notes with this tag

Analysis

1 notes with this tag

Anxiety

1 notes with this tag

Apple

1 notes with this tag

Augmented Intelligence

1 notes with this tag

Book

1 notes with this tag

Canada

1 notes with this tag

Cognition

1 notes with this tag

Collaboration

1 notes with this tag

Cybernetics

1 notes with this tag

Data Science

1 notes with this tag

Design-Principles

1 notes with this tag

Design-Science

1 notes with this tag

Design-Theories

1 notes with this tag

Drafts

1 notes with this tag

Engagement

1 notes with this tag

Facilitation

1 notes with this tag

Gamification

1 notes with this tag

Habits

1 notes with this tag

Health

1 notes with this tag

Highlights, Change, Systems

1 notes with this tag

Highlights, Tech, Design

1 notes with this tag

Impact

1 notes with this tag

IOS

1 notes with this tag

IPad

1 notes with this tag

Knowledge

1 notes with this tag

Knowledge Management

1 notes with this tag

Kumu

1 notes with this tag

Leadership

1 notes with this tag

Learning

1 notes with this tag

Leverage Analysis

1 notes with this tag

Management

1 notes with this tag

Metrics

1 notes with this tag

Music

1 notes with this tag

NotePlan

1 notes with this tag

Open

1 notes with this tag

1 notes with this tag

Personal

1 notes with this tag

PhD

1 notes with this tag

Planning

1 notes with this tag

Practice

1 notes with this tag

Qualitative Analysis

1 notes with this tag

Resources

1 notes with this tag

Reviews

1 notes with this tag

Sci-Fi

1 notes with this tag

Signal

1 notes with this tag

Sketching

1 notes with this tag

Skills

1 notes with this tag

Social

1 notes with this tag

Startups

1 notes with this tag

Students

1 notes with this tag

Systemic Evaluation

1 notes with this tag

Technology

1 notes with this tag

Volatility

1 notes with this tag

Workshops

1 notes with this tag

Writing

1 notes with this tag

Zotero

1 notes with this tag